“It’s one of the things humans do. Not just have a story, but tell a story.”

“Until the lions have their own historians, the history of the hunt will always glorify the hunter.”

“If you don’t like someone’s story, write your own.”

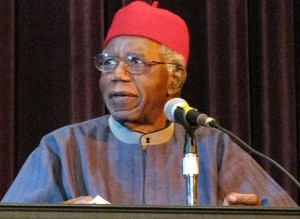

Throughout his life, Nigerian writer Chinua Achebe (1930-2013) affirmed the power of telling one’s own story – and he did so quite powerfully in his landmark 1958 novel, Things Fall Apart.

Last week, I featured Joseph Conrad’s novella, Heart of Darkness (1899/1902). To many readers, probably to Conrad himself, Heart of Darkness seemed to challenge colonialism – but in Things Fall Apart, Achebe makes clear that Conrad still had a thing or two to learn about racism and colonialism.

Indeed, Achebe turns the colonial story on its head, telling the tale not from the perspective of the colonizer but from the vantage point of the colonized – in this case, an Igbo man living in what would become Nigeria. Like all the best heroes, Okonkwo is flawed. Achebe didn’t paint a portrait of the “noble savage” but rather gave us a depiction of a real flesh-and-blood man, filled with arrogance and hubris. In the saga of Okonkwo and the downfall of his fictional village Umuofia, Achebe gives the conquered a voice. Though they are ultimately defeated by colonialism, the lions – rather than the hunter – tell the story.

His success in doing so is evident in the place Things Fall Apart holds in the world’s literary canon. Though a few other African writers had published novels before Achebe, it is Things Fall Apart that is regarded as the “archetypal modern African novel in English,” that marks the birth of the African novel. It has been translated into more than 50 languages and has sold more than 10 million copies. It is frequently anthologized and taught in countless world literature courses around the globe.

The Nigerian-born Achebe was trained at British universities, used the classic novel structure from western literature, and even took the title from Irish poet William Butler Yeats’s 1919 poem, “The Second Coming.” A product himself of colonization, Achebe used the master’s tools to rewrite and challenge the master’s narrative. As he once said, “My weapon is literature.”

Even so, Achebe has been criticized by some for writing in English rather than in Igbo. One source says, “While both African and non-African critics agree that Achebe modeled Things Fall Apart on classic European literature, they disagree about whether his novel upholds a Western model or, in fact, subverts or confronts it.”

In his 1965 essay, “The African Writer and the English Language,” Achebe made clear that his intent was to challenge the colonizers. He said, “English is something you spend your lifetime acquiring, so it would be foolish not to use it. Also, in the logic of colonization and decolonization it is actually a very powerful weapon in the fight to regain what was yours.”

“Achebe has consistently argued for the right of Africans to tell their own story in their own way,” says The New Yorker, “and has attacked the representations of European writers,” Conrad among them. But Achebe:

also did not reject European influence entirely, choosing to write not in his native Igbo but in English, a language that, as he once said, “history has forced down our throat.” In a country with several major languages and more than five hundred smaller ones, establishing a lingua franca was a practical and political necessity. For Achebe, it was also an artistic necessity – a way to give expression to the clash of civilizations that is his enduring theme.

Though the novel is written in English, it is a wholly new English, inflected with Igbo idioms and proverbs. As the National Endowment for the Humanities says, “Things Fall Apart interposes Western linguistic forms and literary traditions with Igbo words and phrases, proverbs, fables, tales, and other elements of African oral and communal storytelling traditions in order to record and preserve African oral traditions as well as to subvert the colonialist language and culture.”

Just what was Achebe trying to dismantle with Igbo-flavored English and a subversion of the western novel form? Hundreds of years of European portrayal of Africans as savages. “The last four or five hundred years of European contact with Africa,” writes The Atlantic Monthly, “produced a body of literature that presented Africa in a very bad light and Africans in very lurid terms.” If you want to get a vivid sense of this, just listen to the excerpt I read last week from Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, in which Africans are described as “savages,” “shapes,” “shadows,” “creatures,” “ants.”

“The language of description of the people in Heart of Darkness is inappropriate,” said Achebe on another occasion. “I realized how terribly, terribly wrong it was to portray my people — any people — from that attitude.” In his famous 1977 essay, “An Image of Africa: Racism in Conrad’s Heart of Darkness,” he wrote: “I am talking about a story in which the very humanity of black people is called in question.”

This practice of presenting Africans as savages, says The Atlantic Monthly, “continued until the Africans themselves, in the middle of the twentieth century, took into their own hands the telling of their story.” Achebe was the writer who led the way in rehumanizing Africans.

African literature has come a long way since Achebe’s tale of Okonkwo and the village of Umuofia. The most recent African literature sensation – Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s 2013 novel, Americanah – extends the African story to three continents and shows the concerns of Africans who have emigrated to Britain and the United States. Like so many African writers, she acknowledges the profound influence Achebe had on her work. “Chinua Achebe,” she says, “will always be important to me because his work influenced not so much my style as my writing philosophy: reading him emboldened me, gave me permission to write about the things I knew well.”

In 1958, Achebe was perhaps not ready to write of the path he and many of his contemporaries took (Achebe eventually and reluctantly settled in the U.S., becoming a professor at Bard College in New York) – but he was the first to say Africans are not “savages” or “ants,” that they are human beings – in all their flawed glory – and that their stories are worth telling and hearing.

I highly recommend Things Fall Apart– it’s a great introduction to African literature. But don’t stop there! I’ll share other African novels and short stories in the months to come.

Join me this week on Pinterest as I pin images and resources related to Chinua Achebe. Take a look around at all my boards – or go straight to “My Favorite Books” board for Chinua Achebe treats.

And don’t forget to leave a comment on this post! You’ll be entered into a monthly drawing to win a StoryWeb T-shirt if you do one of the following. 1) Subscribe to the weekly StoryWeb email, and leave a comment here (or on any other post!). 2) Subscribe to the StoryWeb podcast in iTunes, and leave a review on iTunes. (If you subscribe on iTunes and leave a review there, shoot me an email at linda@thestoryweb.com to let me know you did so!)

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe to StoryWeb in iTunes.Listen to the podcast in Stitcher.

Image credit: Photograph taken by Stuart C. Shapiro, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Chinua_Achebe_-_Buffalo_25Sep2008_crop.jpg