See image credit below.

In 1899, as the soon-to-be-novelist Theodore Dreiser was starting work on Sister Carrie, he was also working on two articles about America’s up-and-coming photographer Alfred Stieglitz. Impressed by Stieglitz’s realistic photography, Dreiser used similar techniques in Sister Carrie, creating “word pictures” to describe city scenes in both Chicago and New York. Relying on photographic elements in these passages, Dreiser emphasized the weather, qualities of light and darkness, and the spectacle aspect of the scenes, thus underlining the stark reality being presented.

Born in 1871 in Terre Haute, Indiana, Dreiser worked until 1899 as a newspaper reporter in Chicago, St. Louis, Toledo, Pittsburgh, and New York and then moved on to magazine work. The amount of work he produced for magazines was phenomenal, with 120 pieces appearing in a three-year period. Much of this journalistic work was not of high quality, later earning Dreiser the reputation of being a “hack” writer. But many of the sketches he turned out for both magazines and newspapers evocatively captured city life during the Gilded Age.

He brought all this – his love of the emerging field of photography and his fascination with the city – into his creation of his 1900 novel, Sister Carrie. The story of a young Wisconsin woman who heads to the big city to make her mark on the world, the novel is just as much about the two cities it presents: Chicago and New York. Picture after picture of city scenes unfold in the narrative.

Many of Dreiser’s word pictures bring to vivid life the cold, snow, and rain – the general gloom and bleakness such unpleasant elements bring. Often these scenes are heavy in their use of black and white, as though the weather had stripped the city of its color. Early in the novel, Dreiser describes Chicago this way: “Once the bright days of summer pass by, a city takes on that sombre garb of grey, wrapt in which it goes about its labours during the long winter. Its endless buildings look grey, its sky and its streets assume a sombre hue; the scattered, leafless trees and wind-blown dust and paper but add to the general solemnity of color.” Similarly, near the end of the novel, Dreiser describes New York City:

Already, at four o’clock, the sombre hue of night was thickening the air. A heavy snow was falling – a fine picking, whipping snow, borne forward by a swift wind in long, thin lines. The streets were bedded with it – six inches of cold, soft carpet, churned to a dirty brown by the crush of teams and the feet of men. Along Broadway men picked their way in ulsters and umbrellas. Along the Bowery, men slouched through it with collars and hats pulled over their ears. In the former thoroughfare business men and travelers were making for comfortable hotels. In the latter, crowds on cold errands shifted past dingy stores, in the deep recesses of which lights were already gleaming. There were early lights in the cable cars, whose usual clatter was reduced by the mantle of the wheels. The whole city was muffled by this fast-thickening mantle.

With these winter scenes, one can’t help but think of such Stieglitz photographs as The Terminal and Winter, Fifth Avenue, both taken in 1893. So connected are Dreiser and Steiglitz, in fact, that Winter, Fifth Avenue graces the cover of the Norton Critical Edition of Sister Carrie. (If you want a hard copy, this is by all means the version to buy!)

In his writings about his approach to fiction, Dreiser said that “True Art Speaks Plainly” (the title of one of his essays). Many years later in an interview, he said that an author needs to be a “sensitive mechanism” so that he can respond to all the life presented to his eyes. “The business of the writer,” he said, “is to hold a mirror up to nature.” Dreiser did that so well for the cities he knew and the people who lived and died in them. To learn more about Dreiser’s life and work, visit Penn Libraries’ Dreiser Web Source, which includes a virtual exhibit on Sister Carrie.

I don’t want to give away the intricate and sometimes hair-raising plot of Sister Carrie, but I will say that the Gilded Age is presented in all its gory glory in the rise of its heroine, Carrie Meeber, and the fall of its antihero, Hurstwood. Sister Carrie – named by The Guardian as one of the best 100 novels ever – is a must-read.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe to StoryWeb in iTunes.Listen to the podcast in Stitcher.

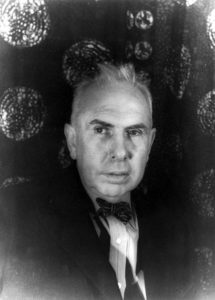

Image Credit: 1933 portrait of Theodore Dreiser taken by Carl Van Vechten, public domain.