In the first section of William Faulkner’s 1929 novel, The Sound and the Fury, Benjy Compson recalls watching his sister, Caddy, climb up a tree so she can peer in the window at their grandmother’s funeral. Caddy and her brothers have just played in the creek, and Caddy’s underwear is wet and muddy. “Caddy was all wet and muddy behind,” Benjy says, and he and his brothers “watched the muddy bottom of her drawers” as she climbed the tree.

The muddy drawers, Faulkner claimed, were the whole secret of the book. Speaking at the University of Virginia in 1959, he said,

It began with the picture of the little girl’s muddy drawers, climbing that tree to look in the parlor window with her brothers that didn’t have the courage to climb the tree waiting to see what she saw. And I tried first to tell it with one brother, and that wasn’t enough. That was Section One. I tried with another brother, and that wasn’t enough. That was Section Two. I tried the third brother, because Caddy was still to me too beautiful and too moving to reduce her to telling what was going on, that it would be more passionate to see her through somebody else’s eyes, I thought. And that failed and I tried myself–the fourth section–to tell what happened, and I still failed.

Much scholarly ink has been spilled about this image of Caddy’s muddy drawers, with most critics arguing that Caddy is a symbol of virginal southern female purity forever stained, an image of the fallen white South. Held up initially as the epitome of the white southern woman on the pedestal, Caddy becomes in this scene the symbol of the decaying Compson family, the white southern plantation family gone bad.

But to my mind, Caddy is so much more. Read another way, she is an image of the robust, adventurous southern woman, the white southern woman to come. Alone among her siblings, she has the courage and audacity to climb the tree and face the truth about her family. (You can read more about my thoughts on “new” southern women in my 1994 book, A Southern Weave of Women: Fiction of the Contemporary South.)

Though Caddy never gets to tell her side of the story, The Sound and the Fury is masterful in so many ways, especially in the fragmented, multi-faceted prism of the three brothers’ views, all of them concerned with Caddy and her muddy drawers.

The first section – the most famous section of them all, I’d say – is told from the point of view of Caddy’s brother Benjy, a 33-year-old, mentally retarded man. For Benjy, the notion of linear, chronological time simply doesn’t exist. Everything is happening now in the same instant. Faulkner wrote this (in)famous section in a stream-of-consciousness narrative, a device developed by Faulkner and his modernist contemporaries. (Think James Joyce’s Ulyssesor Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway

or To the Lighthouse.)

In a stream-of-consciousness narrative, a character’s thoughts are presented exactly as he has them, with no filter. So as Benjy experiences all time as the present, the reader is plunged into a world with no chronology. The result can be disorienting indeed. My advice is to read Benjy’s section and let it wash over you, without trying to make too much “sense” out of it. Later, after you’ve finished the novel, after you’ve met Benjy’s brothers, Quentin and Jason, read various accounts of their sister, Caddy, and seen the white southern family’s neuroses through the eyes of Dilsey, the head black servant on the estate, then you may find that Benjy’s narrative makes a little more sense. Still confused? Re-read Benjy’s section. Feel like you really want to pin things down? Consult a reader’s guide like this one. But don’t skip to the reader’s guide too soon. Instead, try to enter Benjy’s world on your own, and take pleasure in puzzling out his part of the story.

The next two sections – one told by Caddy’s incestuously fascinated brother, Quentin, and the other by her angry, bitter brother, Jason – offer other views of Caddy. Quentin longs to ask, “Did you ever have a sister? Did you? Did you?” And Jason reduces Caddy to one word: “Once a bitch always a bitch, what I say.”

The final section of the novel – known as the “Easter” section because it takes place on Easter Sunday, 1928 – is told as a third-person limited omniscient narrative, with Dilsey as the frame of reference. As the matriarch of the black family that serves the Compsons, Dilsey provides, in some ways, the largest view of Caddy and her severely dysfunctional family. “I’ve seed de first en de last,” Dilsey says. “I seed de beginning, en now I sees de endin.” Though it’s Easter, Faulkner makes clear that there is no redemption or resurrection for the Compson family.

I’ll grant that The Sound and the Fury is hard reading, really hard, some of the most challenging reading out there. But oh, how rich and how rewarding! The novel is so complex, so multi-faceted – and there’s so much more I could say about it. In the end, I believe the reader is rewarded for her hard work – but you’ll have to read it and judge for yourself.

Want more insights into Faulkner and The Sound and the Fury? You’ll find so much to explore on the web!

- An extensive companion website to The Sound and the Fury can be found at Book Drum. There you’ll find “bookmarks” (pictorial and textual snippets relevant to nearly every page of the novel!). You’ll also find a page titled “Setting,” which describes and orients you to Faulkner’s mythical Yoknatawpha County. From this “little postage stamp of native soil,” Faulkner creates a microcosm of the South.

- Take a look at “Keeping Faulkner in the Classroom,” which makes a compelling case for continuing to read and study Faulkner in the 21st There, you’ll also find a list of links to rich Faulkner sites. Especially intriguing is “William Faulkner: The First Hundred Years.”

- There’s a great pictorial bio of Faulkner at the Mississippi Writers Page.

- Learn more about Yoknapatawpha County (including Faulkner’s map of the county) by visiting William Faulkner on the Web. You’ll also discover commentary on The Sound and the Fury as well as a Faulkner “Playroom,” complete with Faulkner trivia and Faulkner quizzes.

- Finally, you’ll want to be sure to take a virtual trip to Faulkner’s Mississippi home, Rowan Oak.

Join me this week on Pinterest as I pin images and resources related to William Faulkner and The Sound and the Fury. Take a look around at all my boards – or go straight to “My Favorite Books” board for William Faulkner treats.

And don’t forget to leave a comment on this post! If you subscribe to the weekly StoryWeb email and leave a comment here, you’ll be entered into a monthly drawing to win a StoryWeb T-shirt.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe to StoryWeb in iTunes.Listen to the podcast in Stitcher.

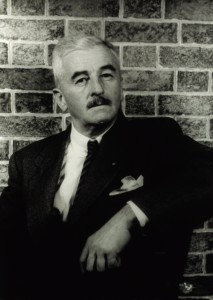

Image Credit: This photo taken by Carl Van Vechten is in the public domain.