See image credit below.

Many Americans know Stephen Crane as the author of the Civil War novel, The Red Badge of Courage, which made Crane famous at the age of 23 when it was serialized in 1894. It was published as a full-length book in 1895. Some know his first novel, Maggie: A Girl of the Streets, or even the harrowing short story “The Open Boat,” based on a real-life experience when Crane was en route to Cuba and spent 30 hours adrift with others in a lifeboat.

Less well known to most readers is Crane’s work as a journalist. Born in 1871 in Newark, New Jersey, Crane floundered around from college (which he didn’t finish) to one vocational pursuit after another. When he found himself drawn to New York City in the 1890s and took work as a newspaper writer, he appeared to have found his calling. Crane would make a peripatetic living for the rest of his short life as a fiction writer and correspondent from various locations throughout the western hemisphere. He filed stories from the Western United States, from Mexico City, from Cuba during the Spanish-American War, and from the Greco-Turkish War front in Greece, where he was joined in his writing by his common-law wife, Cora Crane, recognized as the first woman war correspondent. Stephen Crane died at age 28 of tuberculosis.

But it’s Crane’s writing about New York City in the 1890s that interests me. Working from a home base in nearby Paterson, New Jersey, he made frequent day trips into New York City and spent considerable time in the tenement districts and especially the Bowery. Eventually, he moved into a rooming house in Manhattan. Thus, Crane was one of the journalists – writers, photographers, illustrators – who were on the streets at the height of the Gilded Age. Like Jacob Riis in How the Other Half Lives and like Alfred Stieglitz in such photographs as The Terminal and Winter, Fifth Avenue, Crane offers us a view into New York life at this crucial time in its history.

Perhaps Crane’s most famous piece of journalism is “An Experiment in Misery,” which was first published in 1894 in the New York Press and, in a slightly revised version, as part of The Open Boat and Other Tales of Adventure, a volume Crane published in 1898. In this piece – which to today’s readers will read more like a sketch or even a short story than an objective work of “journalism” – Crane imagines what it would be like to disguise oneself as a Bowery bum and go undercover to explore the realities of that grim life. The lengthy headline tells you all you need to know about journalistic style in the 1890s:

AN EXPERIMENT IN MISERY

An Evening, a Night and a Morning with Those Cast Out.

THE TRAMP LIVES LIKE A KING

But His Royalty, to the Novitiate, Has Drawbacks of Smells and Bugs.

LODGED WITH AN ASSASSIN

A Wonderfully Vivid Picture of a Strange Phase of New York Life,

Written for “The Press” by the Author of “Maggie.”

Newspaper articles on “indigent Americans and the ‘Tramp Menace,’” says the Library of America’s Story of the Week website, were common during the late nineteenth century. A few reporters actually did dress as bums and explore their haunts, but apparently Crane did not himself conduct such an experiment. He did, however, base the imagined experiment on his real-life knowledge of the Bowery, a once-fashionable neighborhood in southern Manhattan now home to saloons, brothels, and rapidly increasing numbers of homeless people in New York City. The result is a vivid account of life as a Bowery bum, as homeless men were known at the time. Just as Crane had never been a soldier in a war yet imagined the Civil War more vividly and “realistically” than any other writer up to that time, so, too, he used his considerable skills of observation and his imagination to conjure up what it would be like to live as a homeless man in New York City.

As it turns out, Crane may have had too much exposure to life in the Bowery. Crane spent time, says one source, in the “saloons, dance halls, brothels and flophouses” of the Bowery. While he claimed he did so for research, his scandalous involvement with prostitutes and madams (most notably Cora Crane, who was operating the Hotel de Dream when Crane met her in Jacksonville, Florida) and other close dealings with the shadier set suggests that Crane was personally drawn to these seedy elements that were so far from his strict upbringing among Methodist ministers and temperance leaders. He said once that the slums were “open and plain, with nothing hidden,” and he seemed to find solace in that.

You can read the original version of “An Experiment in Misery” at WikiSource. Unlike the later version published in The Open Boat and Other Tales of Adventure, the original version published in the newspaper included a “Foreword” and a “Coda” explaining that the sketch presented is an experiment, that a young man disguises himself as a bum to experience that life directly for himself. To read the version published in The Open Boat, get your hands on a copy of Crane: Prose and Poetry, the outstanding collection published by the Library of America.

To learn more about Crane, read the New Yorker’s article “The Red and the Scarlet: The Hectic Career of Stephen Crane.” If you want to go into depth in your exploration of Crane, you can read Paul Sorrentino’s biography, Stephen Crane: A Life of Fire, which tells the story of how Sorrentino and scholar Stanley Wertheim delved deeply into Crane research and archives to debunk common, longstanding myths about Crane.

Although Crane’s writing fell into obscurity for some time after his death, interest in his work was resurrected in the 1920s. He had a particularly strong influence on Ernest Hemingway, who himself was a journalist and a novelist of war.

Next week, I’ll feature a novel by another journalist-turned-novelist: Sister Carrie by Theodore Dreiser. Published in 1900, it is perhaps the masterpiece of the Gilded Age. Stop by next week to learn how Dreiser pulled together the work of Riis, Stieglitz, and Crane to create a complex, multifaceted novel.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe to StoryWeb in iTunes.Listen to the podcast in Stitcher.

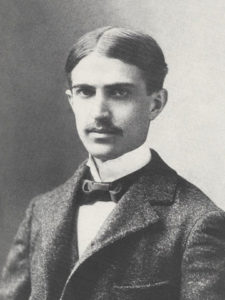

Image Credit: Portrait of Stephen Crane taken in 1896. Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:SCrane2.JPG.