Though it might seem so on the surface, Mark Twain’s 1884 novel, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, is no mere boys’ adventure tale. Scratch the surface just the tiniest bit, and you’ll find one of the most profound explorations of slavery and racism in the history of American literature.

Huck Finn is a morality play about two human beings – one poor, white boy from an abusive home and one black man running for his life. Thrown together in the most unlikely of circumstances, they must depend on each other for their very survival. In the process, the boy – Huck – is forced to rethink what he has learned about black slaves, and the man – Jim – rises in moral stature, both in the eyes of Huck and in the estimation of the reader.

At one point, in a dense fog, the two are separated from their raft and from each other. Each fears the other has died, and when they are reunited their individual responses are telling indeed. Jim, the mature adult, is joyfully relieved that he has found Huck again, and he doesn’t mind saying so. Huck, ever the adolescent (he is 13 years old, after all), turns the event into a prank, perhaps afraid to face the fears he felt at being separated, perhaps permanently, from Jim.

As Huck pulls his prank and Jim realizes that he’s become the butt of Huck’s joke, the moral tables are turned. As a white boy, no matter how poor, Huck would always be seen by his society as superior to the black slave. But in this scene, Jim decidedly takes the moral high road, and the reader sees him as the character with moral integrity, indeed moral superiority.

As Jim says, “Dat truck dah is trash; en trash is what people is dat puts dirt on de head er dey fren’s en makes ’em ashamed.”

Now shamed himself, Huck retreats to the raft’s wigwam and says,

It made me feel so mean I could almost kissed his foot to get him to take it back. It was fifteen minutes before I could work myself up to go and humble myself to [Jim] – but I done it, and I warn’t ever sorry for it afterwards, neither. I didn’t do him no more mean tricks, and I wouldn’t done that one if I’d a knowed it would make him feel that way.

From here on out, Huck faces an ethical dilemma. Should he uphold the mores of his society and turn Jim in to his owners? Or should he respect the humanity of the man who has become his friend and help him escape? In between their numerous escapades, which continue throughout the novel, we watch Huck as he struggles with this choice.

At the novel’s climactic moment, Huck makes what seems to be a definitive decision (“All right, then, I’ll go to hell,” he says, as he vows to stand by his friend), but in the closing chapters, we watch him once again turn Jim into an object of adventure, spurred on by his buddy Tom Sawyer. Perhaps it’s too much to ask a 13-year-old boy to stick with the outcome of a weighty moral decision. Perhaps he can’t become an abolitionist or anti-racist overnight, but instead must “light out for the territory.” It’s a complicated issue, the one Huck faces.

Twain went for the country’s jugular on this one. Written in 1884, it still gets to the heart of the divide that separates our nation. We’re still pained by his use of the “n” word. It’s a difficult word, perhaps the most difficult word Americans know. But from my perspective, Twain was at the very least trying to get Huck’s language correct and arguably even showing the severe limitations we face when we label human beings with words.

Some great considerations of Twain’s use of the word are “Huckleberry Finn and the N-Word Debate” (from “60 Minutes”), “Light Out, Huck, They Still Want to Sivilize You” (from the New York Times), and “Teaching Mark Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” (by Shelley Fisher Fishkin, a noted Twain scholar). Another fantastic resource is “Teaching Twain and Huckleberry Finn with the New York Times,” and you’ll also want to be sure you check out the University of Virginia’s Huck Finn home page. If you want to explore Fishkin’s work, you may want to read Was Huck Black? Mark Twain and African-American Voices.

If you’ve ever been dissuaded from reading Huck Finn, fearing that it was racist trash as a few of its critics have claimed, I urge you to take the time to read the novel. Throughout his career, Twain railed against the corrupting influence of what he called Sunday-school society – and I believe that he saw racism as part and parcel of that corruption. Twain was part of the solution, not part of the problem – and a careful reading of Huck Finn can reveal the depth with which he saw the issue that was central not only to the 19th century but that continues to divide us today.

Join me this week on Pinterest as I pin images and resources related to Mark Twain and Huck Finn. Take a look around at all my boards – or go straight to “My Favorite Books” board for all things Huck Finn!

And don’t forget to leave a comment on this post! If you subscribe to the weekly StoryWeb email and leave a comment here, you’ll be entered into a monthly drawing to win a StoryWeb T-shirt.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe to StoryWeb in iTunes.Subscribe to StoryWeb in Stitcher.

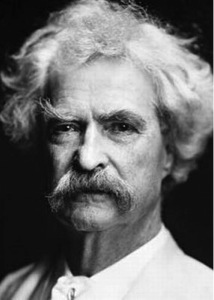

Image credit: This image is in the public domain.