“You have seen how a man was made a slave; you shall see how a slave was made a man.”

These words are at the heart of Frederick Douglass’s 1845 book, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave, Written by Himself. It was the first of three books he would write in his impressive lifetime, the other two being My Bondage and My Freedom

(1855) and Life and Times of Frederick Douglass

(first published in 1881 and revised in 1892).

Used as a tract to promote the abolitionist movement, Douglass’s 1845 Narrative fits squarely within the tradition of slave narratives. William L. Andrews provides a fascinating study of slave narratives in his book, To Tell a Free Story: The First Century of Afro-American Autobiography, 1760-1865. As Andrews points out, slave narratives had to cover three elements: the narrator’s experiences in slavery, his/her heroic journey from slavery to freedom, and his/her subsequent devotion to abolitionist principles and goals. In addition, slave narratives usually traced the narrator’s “development of consciousness,” which leads him/her to “physical revolt” and eventual freedom of body and mind.

Douglass’s Narrative hits nearly all these marks – though he famously refused to detail his physical journey from slavery to freedom. He said he did not want to divulge the secrets of his escape and thereby transform the Underground Railroad to the Upperground Railroad.

But Douglass’s book goes beyond the formula slave narrative. It taps into the language and philosophy of the day, most notably that of Transcendentalism. A careful reading of this book – published in 1845, when Transcendentalism was quickly gaining ground – reveals the echoes of the philosophical movement led by Ralph Waldo Emerson and championed by Henry David Thoreau. In fact, so similar were they in their thinking and in their commitment to the abolitionist movement that Thoreau was once called in to substitute at a speaking engagement Douglass could not make.

In short, I strongly consider Douglass’s Narrative to be a key text of the Transcendentalist movement. Many Transcendentalists – including Bronson Alcott (Louisa May Alcott’s father) – were ardent abolitionists, and Douglass was surely welcome in their circle.

The pivotal scene in Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass is the one in which Douglass fights Mr. Covey, the slavebreaker. In his reflection on the fight, Douglass echoes Transcendentalism as he talks about claiming his manhood – and he also anticipates Malcolm X, who advocated the right of self-defense. Douglass writes:

This battle with Mr. Covey was the turning-point in my career as a slave. It rekindled the few expiring embers of freedom, and revived within me a sense of my own manhood. It recalled the departed self-confidence, and inspired me again with a determination to be free. The gratification afforded by the triumph was a full compensation for whatever else might follow, even death itself. He only can understand the deep satisfaction which I experienced, who has himself repelled by force the bloody arm of slavery. I felt as I never felt before. It was a glorious resurrection, from the tomb of slavery, to the heaven of freedom. My long-crushed spirit rose, cowardice departed, bold defiance took its place; and I now resolved that, however long I might remain a slave in form, the day had passed forever when I could be a slave in fact.

This scene – featured in this week’s audio recording – is one of the most memorable depictions of transformation in all of American literature. More than twenty years ago, I spent quite a bit of time tracing Douglass’s whereabouts on the Eastern Shore of Maryland, where he had been a slave. Then based on my research, I had the good fortune of leading several field trips to Talbot County on the Chesapeake Bay and showing students firsthand where Douglass had become a man.

On the first field trip I led (in 1992), we went to Covey’s farmhouse and stood in the barnyard where Douglass had fought against and triumphed over the slavebreaker. While there, we met descendants of other slaves kept on Covey’s farm. They shared Douglass’s birth surname: Bailey. Until our visit, they had not known of their possible connection to Douglass, had not known he had been a slave on that same farm. Together, we read from Douglass’s Narrative, and we all marveled at the heritage they shared with Talbot County’s most famous son.

There’s so much about Douglass to learn – and you can start by visiting our American Transcendentalism webpage on Douglass where you can explore his time in the Chesapeake Bay region and in Baltimore’s Fells Point neighborhood. You might also enjoy our Frederick Douglass WebQuest, which highlights the Transcendentalists’ commitment to abolitionism. It’s also worth checking out C-SPAN’s American Writers special on Frederick Douglass. Documenting the American South also has extensive Douglass resources.

Ready to read the whole Narrative? An online version can be found at Project Gutenberg. An excellent print edition of Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass is available through Norton Critical Editions (edited by William L. Andrews). The definitive collection is The Oxford Frederick Douglass Reader

, also edited by Andrews. If you want to explore more slave narratives, you’ll definitely want to check out Library of America’s volume on Slave Narratives

. And of course, don’t forget about Andrews’s outstanding study, To Tell a Free Story

.

Join me this week on Pinterest as I pin images and resources related to Frederick Douglass and slave narratives. Take a look around at all my boards – or go straight to “My Favorite Books” board for Frederick Douglass treats.

Don’t forget to leave a comment on this post! You’ll be entered into a monthly drawing to win a StoryWeb T-shirt if you do one of the following. 1) Subscribe to the weekly StoryWeb email, and leave a comment here (or on any other post!). 2) Subscribe to the StoryWeb podcast in iTunes, and leave a review on iTunes. (If you subscribe on iTunes and leave a review there, shoot me an email at linda@thestoryweb.com to let me know you did so!)

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe to StoryWeb in iTunes.Listen to the podcast in Stitcher.

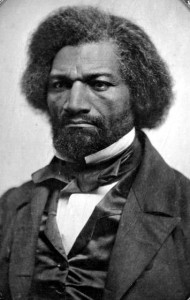

Image Credit: Portrait courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery at the Smithsonian Institution.