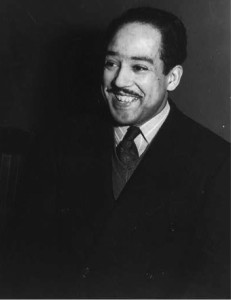

No one has brought music and poetry together better than Langston Hughes. The African American author – born in Joplin, Missouri, in 1902 – brought his adopted home of Harlem to life vividly and memorably in stories, plays, and most notably, poems.

Hughes reveled in the culture of African-descended people throughout the world, as can be seen in the poem “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” (here with a link to an audio recording of Hughes reading the poem). He enjoyed street language, rent parties, the sounds and smells of Harlem.

But without a doubt, his greatest pleasure came from African American music, particularly jazz and blues. Jazz poems were among his favorite to write. A poem like “Deferred” sets up and skillfully uses jazz syncopation in a very short poem. And the collection it opens, Montage of a Dream Deferred (1951), is an improvised, multi-voiced jazz masterpiece in its own right.

Of equal importance to Hughes was the musical form known as “the blues.” Unlike jazz, which features free-flowing riffs and disrupted rhythms, the blues calls for a prescribed rhythm, a single voice repetitively crooning the pain of the human race. So when writing a blues poem, Hughes’s challenge was to take a seemingly simple musical form and show how it can speak to the fullness and depth of the human experience.

He achieves this in his famous 1925 poem, “The Weary Blues,” in which he tells the story of coming across a blues pianist playing and singing on Harlem’s Lenox Avenue. “The Weary Blues” was also the title poem of Hughes’s first collection, published in 1926. “I got the Weary Blues / and I can’t be satisfied,” the musician sings.

Hughes broke new ground in American poetry and in African American culture with his insistence on using poetry as a tool for reaching out to and speaking for the African American community. Unlike his Harlem Renaissance contemporaries, such as Countee Cullen and Claude McKay, he rejected “white” literary forms (such as the sonnet) and instead embraced black vernacular forms as the foundation for his poetry. Drawing on the definitively African American musical forms of jazz and the blues, Hughes was proclaiming proudly and loudly that African Americans had a unique culture worth sharing.

Probably my favorite fun fact about “The Weary Blues” is that it was painted on a wall in the foyer of A’Lelia Walker’s Harlem townhouse at 136th Street near Lenox Avenue. Known as The Dark Tower, Walker’s townhouse served as a literary and arts salon for the cultural phenomenon known as the Harlem Renaissance. On the facing wall was written Countee Cullen’s sonnet, “From the Dark Tower.” So when visitors walked into the Dark Tower, they literally stepped right through the sometimes-bitter disagreement between Cullen and Hughes – and the writers who aligned with them (such as McKay for Cullen and Zora Neale Hurston for Hughes). Cullen and McKay argued that African American writers could best achieve literary prominence by showing that they could write in the most challenging of white literary traditions. Hughes and Hurston took the opposite stance: they said that African American writers and artists would only excel when they drew from the creative energy of their community.

Want my opinion on who won that argument? Just consider which writers are most celebrated today. How familiar are you with the poetry of Countee Cullen and Claude McKay? Have you heard of Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston? I rest my case!

Ready to explore Hughes’s work more fully? The recent reissue of The Weary Blues is a good place to start. If you want to go deeper, consider adding <The Collected Poems of Langston Hughes

to your collection. The Big Sea: An Autobiography

will give you insights into Hughes’s life, as will Selected Letters of Langston Hughes

. True aficionados will want to read Arnold Rampersad’s two-volume biography of Langston Hughes. Volume I of The Life of Langston Hughes

is sub-titled I, Too, Sing America and covers the years 1902-1941. Volume II is sub-titled I Dream a World

and covers the years 1941-1967 (the year of Hughes’s death).

Join me this week on Pinterest as I pin images and resources related to Langston Hughes and the Harlem Renaissance. Take a look around at all my boards – or go straight to “My Favorite Poems” board for Langston Hughes treats.

Don’t forget to leave a comment on this post! You’ll be entered into a monthly drawing to win a StoryWeb T-shirt if you do one of the following. 1) Subscribe to the weekly StoryWeb email, and leave a comment here (or on any other post!). 2) Subscribe to the StoryWeb podcast in iTunes, and leave a review on iTunes. (If you subscribe on iTunes and leave a review there, shoot me an email at linda@thestoryweb.com to let me know you did so!)

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe to StoryWeb in iTunes.Listen to the podcast in Stitcher.

Image Credit: Langston Hughes, photo by Jack Delano (from Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Reproduction #LC-USZ62-43605).