See image credit below.

Mexican painter Frida Kahlo is known for her stunning self-portraits. You might not think of her immediately as a painter who tells stories through her art. Indeed, you could be forgiven if you think of her husband, muralist Diego Rivera, as the more narrative painter of the two. After all, his paintings told tales of the Mexican Revolution.

But Kahlo’s paintings tell a tale – the same tale – over and over again, nearly obsessively, as if Kahlo had a compulsive need to share her story.

For the tale she told so many of her paintings was the devastating effect a serious bus accident had on her body and her simultaneous refusal to let that accident define her life.

The accident she endured – and the injuries that resulted – are almost too gruesome to imagine. As a university student, she was on a bus when it collided with a streetcar. Several people were killed, and though Kahlo survived, she suffered an almost incomprehensible injury: she was impaled – through her pelvis – on an iron handrail.

Kahlo spent the rest of her life recovering from the accident. She was eighteen when she was injured. She was forty-seven when she died. In those intervening decades, she experienced excruciating pain and was sometimes confined to plaster corsets that left her lying on her back for months at a time. As one of her friends said, Kahlo “lived dying.”

Though Kahlo had been at the university to prepare for medical school, during her long recovery she found herself drawn to painting. Ultimately, she was extremely driven to be a painter, and even though she was flat on her back for months at a time, she rigged up a mirror and a canvas and painted portraits of herself as she appeared lying in bed.

Of her approximately two hundred paintings, many were self-portraits – and these are the images that stay with us today. She said, “I paint self-portraits because I am so often alone, because I am the person I know best.”

One of the most compelling of her many self-portraits is “The Two Fridas,” a double self-portrait she painted in 1939, the year she was divorced from Diego Rivera (before remarrying him in 1940). While most of Kahlo’s paintings were small (precisely the opposite of her husband’s grand murals), “The Two Fridas” was her first large-scale painting. It was also the painting for which she received the most money in her lifetime.

The painting indicates a split in Kahlo’s identity. The Frida on the left appears in a Victorian white dress, representing, some art historians have suggested, her paternal German heritage and her European-influenced, elite, privileged upbringing. The Frida on the right appears in the traditional indigenous clothing of a Mexican peasant, suggesting her maternal Mestiza ancestry, which she embraced as a key part of her involvement in the Mexican Revolution. Many Mexican women artists and intellectuals were also dressing in Mexican peasant clothing to emphasize their indigenous ancestry. Dressing this way was an immediate, powerfully visual way to declare one’s allegiance to the Mexican Revolution. Kahlo became known in her art for depicting herself in traditional clothing – and very well known in her life for her embrace of indigenous clothing and accessories. She wore long and colorful skirts and dresses, elaborate headdresses in her hair, and striking traditional jewelry. The reason for the indigenous clothing and jewelry is not hard to understand. The Mexicanidad movement was rejecting European colonialism and elevating the traditional folk culture of Mexico. As Kahlo said, she wished “to be worthy, with my paintings, of the people to whom I belong and to the ideas which strengthen me.”

A striking element in The Two Fridas is the broken blood vessel that connects the hearts of the two Fridas. It is not hard to see Kahlo’s references to her life of constant pain and suffering, a life that was marked by thirty-two separate surgeries to correct the injuries she sustained during the bus accident. Kahlo also indicated that the painting was a way of mourning her separation from Diego Rivera, to make vivid her broken heart, the feeling of being split in two. The Frida in the white dress may be independent and fierce, but the traditional Frida – as encouraged by her husband, whose portrait she holds in her hand – has embraced a revolutionary identity. Which Frida is the real Frida? This search for self-identity was at the center of so much of Kahlo’s work throughout her life. The fact that the two Fridas are set against the background of an intensely stormy sky indicates that this quest for self-understanding caused a great deal of turmoil for Kahlo.

To learn more about Kahlo, you’ll definitely want to watch Frida, a 2002 film starring Salma Hayek as the artist. The film is a good introduction to Kahlo’s larger-than-life tale: her accident and its aftermath; her stormy marriage to Rivera, who was more than twenty years her senior and a very famous artist when he met the then-unknown Kahlo; his love affairs as well as hers, including one with Leon Trotsky; and her ability to hold court and be a very powerful and commanding presence despite her physical limitations. More than anything, though, Frida will introduce you to Kahlo’s marvelous work as a painter.

Another interesting take on the couple known by the Mexican press simply as “Diego and Frida” is Barbara Kingsolver’s novel The Lacuna. Told from the perspective of a fictional assistant to the artists, the novel offers a bird’s-eye view of the famous pair.

While the petite and physically frail Kahlo was largely overshadowed (both literally and figuratively) by her near giant of a husband, interest in her work surged in the late 1970s and has only gained momentum in the years since. The resulting cultural phenomenon is sometimes called “Fridamania” – as her face, her paintings, and her story have swept popular culture. Today, you can buy not only Frida Kahlo posters but also Frida Kahlo home furnishings

, hair accessories

, and clothes

. You can easily find a shower curtain

, an action figure

, a magnetic dress-up play set

, socks

, and of course, calendars

featuring images from her various self-portraits. Interestingly, the Frida Kahlo Corporation controls access to images of the famed artist. Through the corporation, you can get credit cards, tequilla, and more – all emblazoned with Kahlo’s licensed image.

To round out your exploration of this phenomenal Mexican artist, you’ll want to visit the official Frida Kahlo website. Other valuable resources on Kahlo are the excellent Wikipedia post about her; an entry on Biography.com; and the BBC’s article “13 Things You Didn’t Know about Frida Kahlo.” To go in depth, check out Hayden Herrera’s biography, Frida. And most importantly, to view the paintings, you’ll want to visit the galleries at FridaKahlo.org, the Frida Kahlo Foundation, and WikiArt.

“I am not sick. I am broken,” Kahlo said near the end of her life. “But I am happy to be alive as long as I can paint.” The last words in her diary were: “I hope the leaving is joyful; and I hope never to return.”

Watch:Watch actual footage of Frida Kahlo and her husband, Diego Rivera. Then watch a clip from Julie Taymor’s 2002 film Frida. In this scene, Frida attends her Mexican exhibition against all odds.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe to StoryWeb in iTunes.Listen to the podcast in Stitcher.

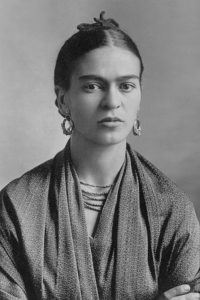

Image Credit: Portrait of Frida Kahlo taken by her father in 1932 when she was twenty-five. Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Frida_Kahlo,_by_Guillermo_Kahlo.jpg.