See image credit below.

In the 1890s, as Alfred Stieglitz was beginning his career, photographers were fighting for artistic recognition. Photographers who wanted to go beyond “mere” journalism or documentary photography had to show their critics the value of their “mechanistic” art. Photographers like Stieglitz were trying to prove to skeptics that the camera could be used not only as a journalistic tool (as Jacob Riis used it in How the Other Half Lives) but that photographs could also have value as art. Stieglitz was unquestionably the leader of the movement to gain artistic recognition for photography.

A pioneer in subject matter, technique, and treatment, Stieglitz shot many “firsts,” among them the first snow photograph, Winter, Fifth Avenue (1893), the first rain photo, A Wet Day on the Boulevard [Paris] (1894), and the first night shot, Reflections – Night [New York] (1896). In 1897, Stieglitz published Picturesque Bits of New York, a volume of his New York scenes; it sold for the then-whopping price of $15.

Stieglitz was concerned with both seeing life as it was and interpreting it morally. Scholar Doris Bry says of him: “To define and fix a moment of reality, to realize the potential of black and white, through photography, fascinated Stieglitz.” But objectivity to Stieglitz was not enough. In a 1908 article in the New York Herald, Stieglitz stressed the importance of the “personal touch” and the “individual expression” of the artist. He said, “I saw what others were doing was to make hard, cold copies of hard, cold subjects in hard, cold light. . . . I did not see why a photograph should not be a work of art, and I studied to make it one.”

Though Stieglitz hailed from Hoboken, New Jersey, New York was his adopted city. As Bry says, “he came to love [the city], it became home to him.” Art critic Neil Leonard says, “Stieglitz’s photographs of these years held strong emotional meaning for him, yet they realistically captured . . . the sights, rhythms, and moods of the city.”

Two of Stieglitz’s New York photos are particularly compelling to me, both shot in 1893: The Terminal and Winter, Fifth Avenue. Stieglitz said, “From 1893 to 1895 I often walked the streets of New York downtown, near the East River, taking my hand camera with me.” According to The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Stieglitz’s small Folmer and Schwing 4 x 5 plate film camera was “an instrument not considered at the time to be worthy of artistic photography.” Stieglitz threw away his “unwieldy” 8 x 10 view camera and its tripod, choosing the 4 x 5 camera, which, says The Met, “gave [him] greater freedom and mobility to roam the city and respond quickly to the ever-changing street life around him.”

See image credit below.

The Terminal was captured at the southern end of the Harlem streetcar line, which traveled up and down Fifth Avenue. One day, said Stieglitz, “I found myself in front of the old Post Office. . . . It was extremely cold. Snow lay on the ground. A driver in a rubber coat was watering his steaming car horses. How fortunate the horses seemed, having a human being to tend them. The steaming horses being watered on a cold winter day, the snow-covered streets . . . [expressed] my own sense of loneliness in my own country.” In another description of The Terminal, Stieglitz said, “I used to walk around the streets disconsolately, until one night during a blizzard, I happened to see a man, watering a couple of horse-car horses, and I thought, ‘Well, there at any rate is the human touch;’ that made me feel better.” Of the same incident, Stieglitz told biographer Dorothy Norman, “There seemed to me to be something closely related to my deepest feeling in what I saw . . . and I decided to photograph what was within me.”

See image credit below.

Winter, Fifth Avenue was taken the same year, also with a 4 x 5 box camera. Journalist and novelist Theodore Dreiser, who was heavily influenced by Stieglitz, said of this photograph: “The driving sleet and uncomfortable atmosphere issued out of the picture with uncomfortable persuasion. It had the tone of reality.” What seems to have impressed Dreiser most about Stieglitz’s photography, however, was the huge amount of time and effort Stieglitz took in making the final prints. Patience was necessary at all stages: setting up the scene, working with the negative, making the print. Indeed, according to The Art Story website, Stieglitz “stalked Fifth Avenue for three frigid hours waiting for the perfect moment.” Stieglitz himself told the story this way:

On Washington’s birthday in 1893, a great blizzard raged in New York. I stood on a corner of Fifth Avenue, watching the lumbering stagecoaches appear through the blinding snow and move northward on the avenue. The question formed itself: could what I was experiencing, seeing, be put down with the slot plates and lenses available? The light was dim. Knowing that where there is light, one can photograph, I decided to make an exposure. After three hours of standing in the blinding snow, I saw the stagecoach come struggling up the street with the driver lashing his horses onward. At that point, I was nearly out of my head, but I got the exposure I wanted.

Often, the negatives produced were discouraging. Such was the case with Winter, Fifth Avenue, the original negative of which was so blurry that a fellow photographer said, “For God’s sake, Stieglitz, throw that thing away.” But Stieglitz focused on a portion of the negative that he felt was usable and managed to manipulate it in the darkroom until he got what he wanted. The result is a stunning photograph indeed.

Good overviews of Stieglitz’s work can be found at The Metropolitan Museum of Art website and the PBS American Masters website. The New York Times review of “Alfred Stieglitz New York,” a 2010 exhibit at the Seaport Museum, offers additional insights into Stieglitz’s depictions of his adopted city.

Books you might want to add to your collection include Alfred Stieglitz: Masters of Photography Series (which features The Terminal on the cover) and Alfred Stieglitz: Photographs & Writings

. Alfred Stieglitz: A Biography

offers a comprehensive look at Stieglitz’s immense influence on photography.

To explore the artistic connections between Stieglitz and his wife, painter Georgia O’Keeffe, check out Two Lives: A Conversation in Paintings and Photographs – and to learn more about their personal lives, dip into My Faraway One: Selected Letters of Georgia O’Keeffe and Alfred Stieglitz

.

Tune in next week for an exploration of Stephen Crane and his journalistic essays about New York life during the 1890s.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe to StoryWeb in iTunes.Listen to the podcast in Stitcher.

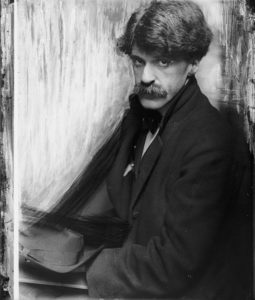

Image Credits: 1902 portrait of Alfred Stieglitz; The Terminal (1893); and Winter, Fifth Avenue (1893).