Alice Walker’s 1974 essay, “In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens,” begins with a mystery: how did Alice Walker, a black woman from a poor tenant farm family in Georgia, become a writer? Where did her storytelling ability and her rich creativity come from?

Walker puzzles over this as a young woman, until one day she is standing in one of the Smithsonian museums, looking at a quilt displayed with a note that reads, “an anonymous Black woman in Alabama, a hundred years ago.”

Right then, Walker knew exactly where her artistic sense had come from: her mother and her grandmother and the women who came before them.

Though they had not received the education Walker had been privileged to earn at Spelman College and Sarah Lawrence College, they were every bit as creative as she was discovering herself to be. In her grandmother’s quilts, in her mother’s lavish gardens were bountiful expressions of artistry – expressed through the vehicles that were available to them as poor, uneducated black women in the Jim Crow South.

Walker’s recognition of her foremothers’ creativity leads her to ruminate on women’s artistic traditions in general – from the domestic arts of quilt making and gardening to the few written texts that have been passed down by women. Walker sings the praises of Phillis Wheatley, the slave who is widely recognized as the first African American writer, male or female, and she wonders about Frances Harper, Nella Larsen, and her patron saint, Zora Neale Hurston.

And Walker realizes one other important lesson: that the women who went before her paved the way for her own very different life. The poem that concludes the essay reads, in part:

They were women then

My mama’s generation . . .

How they knew what we

Must know

Without knowing a page

Of it

Themselves.

I’ve always identified strongly with these lines, for my mother and grandmothers also made a way for me. In fact, those lines speak so strongly to me that they form the epigraph to my first book, A Southern Weave of Women: Fiction of the Contemporary South.

Ultimately, Walker’s discovery is one that applies to all women, particularly women of color. That is why the essay is titled “In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens,” rather than “In Search of My Mother’s Garden.” For Walker recognized that all of us – particularly the women who read the essay when it first appeared in Ms. Magazine – need to herald the poetry and artistry in our mothers’ and grandmothers’ lives, need to see the seeds of her own.

Many years ago, one of my former students – Tiffany Lawrence, a member of the West Virginia House of Delegates – gave me a little, locket-sized mirror. On the back was engraved “In search of my mother’s garden, I found my own.” What a perfect way to memorialize and celebrate Walker’s essay! (Thanks, Tiffany!)

Walker’s essay was a manifesto of sorts in 1974, and it ushered forth a rich era in women’s writing. You can read it – along with her other early prose – in In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens: Womanist Prose.

Don’t forget to leave a comment on this post! If you subscribe to the weekly StoryWeb email and leave a comment here, you’ll be entered into a monthly drawing to win a StoryWeb T-shirt.

Listen:Listen as audiobook narrator Elizabeth Klett reads “In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens” in its entirety. The clip runs 23:35.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe to StoryWeb in iTunes.Subscribe to StoryWeb in Stitcher.

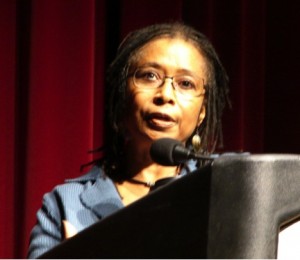

Photo by Virginia DeBolt. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Alice_Walker.jpg.