Walt Whitman, America’s great poet, is not usually thought of as a storyteller – but in his celebration of the diverse American people, the individuals he names from the prostitute to the president, he tells the story of the entire country. Leaves of Grass can be seen as an American epic.

No one reveled in the power of words on the page more than Walt Whitman. He truly, literally, fervently believed that words on the page could link people across place and, especially, across time. Nowhere is this truer than in “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry,” first published in 1856 and finally modified in 1881.

Reading in 2015, the reader feels Whitman’s experience and emotions as he commutes from Brooklyn to lower Manhattan on the Brooklyn Ferry.

This poem is often assigned in high school and college English classes (and for good reason: it is a knock-the-ball-out-of-the-park, great poem!). But if you read this poem merely to finish an assignment and don’t really absorb what it’s saying, you’ll miss so much – the real deal Whitman offers.

He writes,

It avails not, neither time nor place – distance avails not;

am with you, you men and women of a generation, or ever so many generations hence;

Just as you feel when you look on the river and sky, so I felt;

Just as any of you is one of a living crowd, I was one of a crowd;

Just as you are refresh’d by the gladness of the river and the bright flow, I was refresh’d;

Just as you stand and lean on the rail, yet hurry with the swift current, I stood, yet was hurried;

Just as you look on the numberlass masts of ships, and the thick-stem’d pipes of steamboats, I look’d.

Oh, how I love these lines! For Whitman is speaking to me (and to you!) directly across time. He writes of the daily commute, all those people he sees crowding onto the ferry, and he thinks of all the people to come decades and centuries after him who will also push their way through the daily grind. And he uses the words on the page – his poem – to speak to us in that moment.

Twice, I have had the privilege of taking students to walk across the Brooklyn Bridge (the Brooklyn Ferry is no more, but the Brooklyn Bridge is a fine replacement for it). Each time, we walked halfway out to the very center of the bridge, and there together read the words of “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry” aloud. Lusty young Walt, proud old Whitman speaking to us as we stood there in the 21st century, seeing the same river and sky he saw. We were post-9/11. What we saw and thought about was so different from what Whitman had experienced – but it was also essentially the same. We were one of a crowd. We were refreshed. We looked at the urban scene spread all around us.

Whitman does speak to us, still today more than 150 years after he put pen to paper. “It avails not, neither time or place – distance avails not.”

Ready for more Whitman? There are so many great editions of Leaves of Grass that it’s hard to choose just one, but The Complete Poems is a good starting place – and Justin Kaplan’s biography

is great if you want to know more about Whitman’s life. If you’re curious about my walks on the Brooklyn Bridge with my students, visit our American Transcendentalism Online Travel Guide, and check out our Whitman page (created by my former student Deidre Morrison). This page – and our Whitman WebQuest – focus on Whitman’s celebration of New York.

Join me this week on Pinterest as I pin images and resources related to Walt Whitman. Take a look around at all my boards – or go straight to “My Favorite Poems” board for Walt Whitman treats.

Don’t forget to leave a comment on this post! You’ll be entered into a monthly drawing to win a StoryWeb T-shirt if you do one of the following. 1) Subscribe to the weekly StoryWeb email, and leave a comment here (or on any other post!). 2) Subscribe to the StoryWeb podcast in iTunes, and leave a review on iTunes. (If you subscribe on iTunes and leave a review there, shoot me an email at linda@thestoryweb.com to let me know you did so!)

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe to StoryWeb in iTunes.Listen to the podcast in Stitcher.

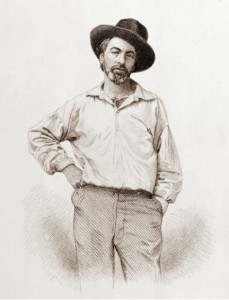

Image credit: This image – the sketch that appeared in the inaugural 1855 edition of Leaves of Grass – is in the public domain.