See image credit below.

It has been more than 25 years since I read Rev. James H. Cone’s book Martin & Malcolm & America: A Dream or a Nightmare. I was teaching an English 101 course focused on the writing of the Civil Rights Movement, and I wanted to learn more about Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and Malcolm X and to understand better the relationship between them, the intersection points, if any, between them. Of course, I’d already read Dr. King’s “I Have a Dream” speech and his landmark “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” and I’d read The Autobiography of Malcolm X.

But it was James H. Cone’s 1991 book, Martin & Malcolm & America, that helped me to deeply understand how the two seemingly diametrically opposed civil rights leaders were actually two sides of the same coin. There was so much more to say than that Dr. King preached nonviolence and that Malcolm X advocated violence. Indeed, it was not even accurate to say that Malcolm X “advocated violence.” It was more that he advocated or understood the need for self-defense. Particularly in his softened views after his pilgrimage to Africa and to Mecca, Malcolm X embraced a position of love as much as Dr. King did.

Cone’s book tells the full story of Dr. King and the full story of Malcolm X and the story of their evolving relationship with each other’s viewpoints. It helped me to realize fully and deeply the important and crucial role both of these leaders played in the Civil Rights Movement as their messages resonated against each other, as they responded to each other’s critique and moved closer to each other’s ways of thinking.

It is far too easy for Americans today to embrace King’s words, to share in his vision of an American dream of racial justice and equality. Americans find King’s words inspiring – but also in many ways palatable, manageable, acceptable.

See image credit below.

But many of us are still rattled by Malcolm X’s direct, hard-hitting, even harsh ideas, his assessment that blacks were living in a nightmare realized. In his earlier days, he denounced whites as the devil, though in later days he brought more love to his view of white Americans. Still, his words – both pre- and post-Mecca – are raw and unfiltered. They do give African Americans the right to fight back in self-defense. After reading and absorbing Malcolm X’s teachings, it is impossible not to see Frederick Douglass’s fight against the slave breaker Mr. Covey in any other light. He was fighting back in self-defense, just as Malcolm X would have called him to do. He was literally fighting for his life.

Rev. James H. Cone, who was a minister during the Civil Rights era, has been a professor at Union Theological Seminary in New York City since 1970. Though you might not know his name, rest assured he is a recognized intellectual leader in the fight for justice for African Americans. In a 2008 interview with Terry Gross on Fresh Air, Cone explains his theory of “black liberation theology,” which draws inspiration from both Dr. King and Malcolm X, as “mainly a theology that sees God as concerned with the poor and the weak.”

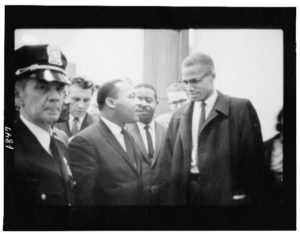

Dr. King and Malcolm X met only once – and that was quite accidentally when they ran into each other in the halls of the U.S. Capitol building in March 1964. But their lives and philosophies and teachings influenced each other more than most of us know. If you want an excellent introduction to and exploration of the Civil Rights Movement and its two seemingly different leaders, I encourage you to read Martin & Malcolm & America, an outstanding comparative intellectual biography in every way. It changed my thinking and understanding profoundly and fundamentally more than a quarter century ago.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe to StoryWeb in iTunes.Listen to the podcast in Stitcher.

Now! Listen on Spotify!

Image Credits: Top: 2009 photo of Rev. James H. Cone, used with permission, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:JamesHalCone.jpg; Bottom: Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and Malcolm X meet each other in person for the only time in their lives in the U.S. Capitol building on March 26, 1964, Library of Congress, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/resource/cph.3d01847/.