See image credit below.

“I believe that unarmed truth and unconditional love will have the final word in reality. This is why right temporarily defeated is stronger than evil triumphant.”

So said Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., on December 10, 1964, as he accepted the Nobel Peace Prize. At 35 years old, he was the youngest person ever to have been awarded the prize.

Sixteen months earlier on August 28, 1963, Dr. King had helped lead what is perhaps still the greatest people’s march on Washington – an iconic “mountaintop” moment in the centuries-long struggle for African American freedom, rights, and dignity. Over a quarter of a million black and white Americans gathered in the nation’s capital one hundred years after President Abraham Lincoln freed the slaves by issuing the Emancipation Proclamation.

The “I Have a Dream” speech Dr. King gave that day is equally iconic. Just twelve hours before he was going to give the speech, Dr. King didn’t yet know what he was going to say. But then as he took the stage, the words that had been simmering, brewing, and forming for the last several months finally took shape. The resulting impassioned speech is considered by many to be the greatest American speech of the twentieth century.

Dr. King was, of course, known as a powerful orator, a preacher who had found his way into being a spokesperson and leader for the Civil Rights Movement. In his sermons, speeches, essays, and letters, he drew upon multilayered rhetorical traditions, weaving together Biblical references and cadences, drawing from a rich African American oral culture, and signifying on key documents and speeches in American history, from the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution to the Emancipation Proclamation and the Gettysburg Address. What emerged from these many threads was Dr. King’s own uniquely powerful message and his stunning delivery.

But Dr. King hadn’t planned his “I Have a Dream” speech. In the hours before the address, he wrote some remarks. He began his speech, and it was powerful, effective. But near the end of his speech, African American gospel singer Mahalia Jackson, who had performed “I Been ‘Buked and I Been Scorned” before Dr. King gave his speech, spoke up. As she listened to Dr. King talk, she thought back to a speech he had given in Detroit earlier that year, a speech in which he had sounded the “dream” refrain he had been preaching since 1960.

As Dr. King spoke from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, Jackson called out, “Tell ‘em about the dream, Martin!” And thus the glorious, prophetic “I have a dream” riff was born. Dr. King said in part:

I say to you today, my friends, so even though we face the difficulties of today and tomorrow, I still have a dream. It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream. I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: “We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men are created equal.”

I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave-owners will be able to sit down together at a table of brotherhood.

I have a dream that one day even the state of Mississippi, a state, sweltering with the heat of injustice – sweltering with the heat of oppression, will be transformed into an oasis of freedom and justice.

I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.

I have a dream today!

Then, as he evoked the lyrics of “My Country, ‘Tis of Thee,” he called out, “Let freedom ring”:

Let freedom ring from Stone Mountain of Georgia.

Let freedom ring from Lookout Mountain of Tennessee.

Let freedom ring from every hill and every molehill of Mississippi, from every mountainside, let freedom ring!

“When this happens,” Dr. King said as he ended the speech, “when we allow freedom to ring, when we let it ring from every village and every hamlet, from every state and every city, we will be able to speed up that day when all of God’s children, black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual: ‘Free at last! Free at last! thank God Almighty, we are free at last!’”

To learn more about the evolution, history, and creation of this iconic speech, check out The Guardian’s article “Martin Luther King: The Story Behind His ‘I Have a Dream’ Speech.” To learn more about Dr. King’s life, work, and legacy, visit The King Center, where you can read other Americans’ dreams and add your own. If you’d like to add a volume of Dr. King’s work to your collection, you might purchase I Have a Dream: Writings and Speeches That Changed the World

. And to share Dr. King’s speech with the children in your life, you’ll want to have a copy of the illustrated book I Have a Dream

. For more on the March on Washington, visit the companion site to the PBS documentary series Eyes on the Prize, where you can also read the speech Civil Rights leader John Lewis gave that day.

In 2017, more than 50 years after that hot August day, as we celebrate Dr. King’s legacy on this important holiday, many of us are hurting, wondering if the nation will soon lose the loving ground we have worked so hard to claim for all American citizens.

As we listen to and reflect on King’s speech, we recognize that #blacklivesmatter, and we mourn that such a movement should still be so needed.

As we listen to Dr. King’s speech, we wonder how a lifelong freedom fighter like U.S. Representative John Lewis can be belittled for being “all talk, no action.”

As we listen to Dr. King’s speech, we anticipate the upcoming Women’s March on Washington and parallel marches in cities across the country.

As we listen to Dr. King’s speech, we hear the echoes of Langston Hughes’s poem “Harlem,” which asks “What happens to a dream deferred?” Hughes named the dream deferred in 1951. Dr. King called out a galvanizing vision of his dream more than a decade later.

Looked at in one way – with the events of recent years still unresolved, with racialized trauma in places like Ferguson, Baltimore, and Charleston, and with the names of Michael Brown, Trayvon Martin, Tamir Rice, Freddie Gray, Sharon Bland, and Eric Garner on our minds and in our hearts – it might seem that Dr. King’s dream of full equality, full dignity, full opportunity for all God’s children is further than ever from being realized.

But as we are tempted to sink into despair over the changes our country is currently witnessing, I come back again and again to Dr. King’s statement in the Nobel Peace Prize speech:

“I believe that unarmed truth and unconditional love will have the final word in reality. This is why right temporarily defeated is stronger than evil triumphant.”

Dr. King’s words call us to stand together in that space of unarmed truth and unconditional love and to keep standing in that space in every way we can, knowing that love will have the final word in reality.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe to StoryWeb in iTunes.Listen to the podcast in Stitcher.

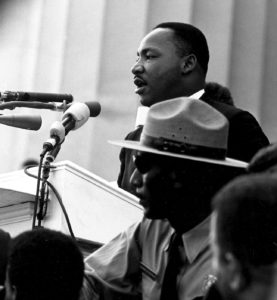

Image Credit: Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., giving his “I Have a Dream” speech, National Archives and Records Administration, public domain, https://catalog.archives.gov/id/542069/.